Confined Space: Managing Exposures

There is a data gap with the instruments used –- intermittent or continuous -- as well as the records resulting from these devices.

- By Jeffrey Lewis

- Nov 01, 2014

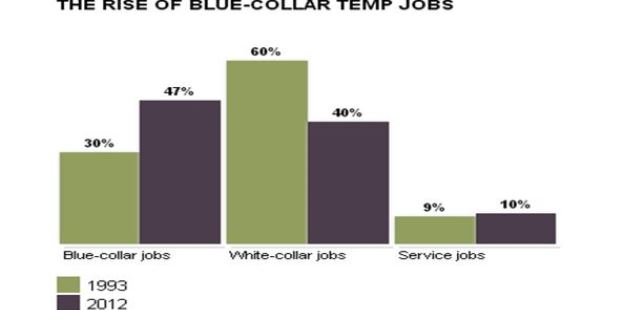

Michael Grabell1 writes that, across America, temporary workers have become the mainstay of the economy. He states that the Labor Department reported in June 2013 that there were more than 2.7 million temporary workers and that temps represent almost one-fifth of the total job growth since the recession ended in mid-2009. According to the American staffing industry, 47 percent of all jobs are temporary blue collar ones, with an upward trend for this category.

"The temp system insulates the host companies from workers' compensation claims, unemployment taxes, union drives and the duty to ensure that their workers are citizens or legal immigrants. In turn, the temps suffer high injury rates, according to federal officials and academic studies, and many of them endure hours of unpaid waiting and face fees that depress their pay below minimum wage. A ProPublica analysis of millions of workers' compensation claims shows that, in five states representing more than a fifth of the U.S. population, temps face a significantly greater risk of getting injured on the job than permanent employees."2

"The temp system insulates the host companies from workers' compensation claims, unemployment taxes, union drives and the duty to ensure that their workers are citizens or legal immigrants. In turn, the temps suffer high injury rates, according to federal officials and academic studies, and many of them endure hours of unpaid waiting and face fees that depress their pay below minimum wage. A ProPublica analysis of millions of workers' compensation claims shows that, in five states representing more than a fifth of the U.S. population, temps face a significantly greater risk of getting injured on the job than permanent employees."2

Production helpers represent the highest percentage of temporary workers (29 percent).3 There is cause for concern because the trend represents the willingness to cut corners, resulting in the stated risk of injuries. In confined space, contracting is part of the landscape and temporary/transient workers are becoming the likely source of labor. Companies need to look beyond the savings on workers compensation and other costs when contractors use temporary workers. They need to recognize that if contractors use temporary workers, they are still liable for the long term toxic exposures of the workers injured on the job at their facility.

Types of Injuries

In the current practice of permit required confined space there is the potential for short-term and long-term gas related injuries:

Short term

During the course of confined space activity, injury to the entrant may occur. Typically, treatment is provided by standby crews (required by the confined space regulations) or fire departments. According to Michael P. Wilson, et al.,4 57 percent of employers call a fire department out when confined space incidents occur.

In July 2013, the City of Portland, Ore., was granted a SAFER grant5 of $1.04 million by the Department of Homeland Security for developing a specialized confined space rescue crew.

Even as first responders suffer injury in attempting rescue,6 there is no means to identify the status of the gas condition on a continuous basis before the rescuers' entry into the confined space. Continuous gas meters, where used, are in the confined space with the entrant and do not help first responders. Records of intermittent gas readings do not provide a trend of information to indicate continuously safe conditions, which may have caused the incident in the first place.

Long term

There are types of gas injuries that are not immediate; it is typical for confined space rescue that injury can occur sometime in the future.

Some VOCs are acutely toxic at low concentrations and most are chronically toxic, with symptoms that may not become fully manifest for years. Exposure can be via skin or eye contact with liquid or aerosol droplets, or via inhalation of VOC vapors.

Inhalation can cause respiratory tract irritation (acute or chronic), as well as effects on the nervous system, such as dizziness, headaches, and other long-term neurological symptoms. Long-term neurological symptoms can include diminished cognition, memory, reaction time, and hand/eye and foot/eye coordination, as well as balance and gait disturbances. Exposure also can lead to mood disorders, with depression, irritability, and fatigue being common symptoms. Peripheral neurotoxicity effects include tremors and diminished fine and gross motor movements. VOCs have also been implicated in kidney damage and immunological problems, including increased cancer rates.7

Because of the likelihood of manifested injuries at a later date, statutory prescribed "bearable" conditions are defined to avoid the threat of these gases. The engineering methodology to manage the personnel within the limits is a challenge.

Exposure Challenges

The entrant's permissible limits on exposure are listed under the OSHA enforceable Permissible Exposure Limits (PELs)8/Occupational Exposure Limit (OELs), which provide for Long Term Exposure Limits (LTEL), Short Term Exposure Limits, (STEL) and Ceiling Limits.

The instantaneous concentrations may exceed the STEL value as long as they never exceed the ceiling, and the 15-minute running average never exceeds the STEL limit. If the STEL alarm is reached, the worker must be removed from STEL level exposure for at least one hour. Workers can be exposed to a maximum of four STEL periods per eight-hour shift, with at least one hour between exposure periods.9 Records are established during the period of the confined space exercise.

Records are needed by companies to verify that the exposure limits are maintained by their representatives. These records need to be kept over the long term of 30 years as required by law (1910.1020), for potential redress on the long-term impact of exposure. Records are also important to companies to ensure their execution of confined space management is within the law. They may need to prove that personnel were managed within the prescribed exposure limits.

Recordkeeping Methods

Two recordkeeping methods are practiced, form permitting and attendant records.

A review of any number of confined space paper permits shows many do not record prescribed requirements because there are no fields in which to input exposure/rest time information on the form by the attendant. For example:

- NASA C-199C (December 11)

- JPL 2 2702 7/09

- CALTRAN – Confined space 2013 - Form HS0040

These forms are typically used industrywide. They do not record entry/exit times to calculate exposure times at concentration levels for the entrant or rest periods by the attendant. Generally, these forms are driven by intermittent gas detection readings. There is no direct correlation at the time of the intermittent gas readings and the instant the critical gas concentrations are reached for measuring STEL.

Continuous Gas Detectors

These are fitted with alarms and log events. They support regulatory values of PELs, LTELs, and STELs and are worn by the entrant. Although sounding the alarm, the meter does not enable the attendant to have the information to manage the entrant’s exposure and rest time. Moreover, management cannot determine or prove from records -– say, 20 years into the future -- whether the alarms were on or not.

The data logging provided by entrants' gas meters is reviewed after the fact at a later time, if an analysis is done, to record the alarm start/stop times – the exposure time. It does not offer the attendant an opportunity to manage the exposure times with records on an ongoing basis, during the course of managing the space for exposure time. The damage is already done to the entrant when the data logs are downloaded at a later time. The data log may record the readings, but confirmation that alarms are set at critical PEL concentrations for logging is not ensured. More importantly, traceability between records and a specific entrant is unlikely in the present or in later years.

Singly or combined, forms or continuous gas detectors are not suitable as an effective strategy for preventing and/or proving that an entrant or rescue team member did not experience the effects of short- or long-term gas exposure.

Toxic Torts

A toxic tort is a lawsuit in which the injured party claims that exposure to chemicals caused his injury or disease. Organizations require a systematic method to protect workers from the consequences of the exposure dangers. Proof from records is needed to demonstrate that at the organization's facility, the employee always worked under the prescribed PEL safe conditions. The required records need to demonstrate:

- Named entrants did not exceed the recommended STEL limits, with real-time continuous gas detection

- Named entrants afforded the recommended rest period.

- Named entrants did not have entry on more than the prescribed number of occasions.

There is a data gap with the instruments used –- intermittent or continuous -- as well as the records resulting from these devices. This gap can be exploited because of a lack of evidence to demonstrate OSHA compliance, as it pertains to an individual worker. This can result in liability or citations if OSHA inspects records anytime during the 30-year period. The attendant, under current methods, does not have tools with the capability to manage the entrant's exposure time and rest periods in order to facilitate records for the years ahead. The practice needs to be upgraded to capture the respective parameters. Companies need assurances that entrants are protected over the long term.

Conclusion

Companies are bound by regulations to protect employees on their premises. With a shift to transient workers, indications are an upward trend of injuries will occur due to the influx of inexperienced temporary workers. When confined space workers are transient, over the long term there is no evidence where exposure occurred for chemical exposure diseases. Because workers do not have records, the mandatory 30-year records by companies are required to prove compliance. The present type of records does not enable the attendant's management of the confined space to demonstrate that long-term regulatory requirements are met. Companies need protection through proper records to prove compliance to be absolved from potential toxic tort issues.

References

1. June 27, 2013, ProPublica.

2. Michael Grabell, Olga Pierce, and Jeff Larson, ProPublica, Dec. 18, 2013.

3. June 27, 2013, ProPublica.

4. Journal of Occupational and Environmental Hygiene, Feb 2012, page 126.

5. http://www.portlandoregon.gov/fire/article/473388.

6. http://www.slate.com/articles/health_and_science/science/2013/05/rescuers_turning_into_victims_lessons_from_first_responders_on_saving_people.html.

7. Robert Henderson, then vice president, business development for BW Technologies, stated in an article, "Measuring, Solvent, Fuel and VOC Vapor."

8. https://www.osha.gov/dsg/topics/pel/.

9. RAE Systems TN 119 rev 2 wh.11-05.

This article originally appeared in the November 2014 issue of Occupational Health & Safety.