Refreshing on the Basics of Noise and Hearing Conservation

Understanding what the rules are is only half of the battle with noise. The other half is assessing noise levels and utilizing effective controls.

Occupational noise exposure and hearing conservation programs can be one of the most elusive and oftentimes one of the most challenging programs to manage in the industrial setting. As safety professionals, we need to become more aware and better versed in occupational noise exposure and how it affects diverse workforces, but first, let's look at the numbers.

According to the Occupational Safety and Health Administration, more than 20 million workers are exposed to hazardous levels of noise at work. Employers were cited nearly $1.5 million in federal OSHA citations in 2017, and workers' compensation payouts cost another $242 million. Unlike other injuries, hearing loss is hard to see and diagnose with the naked eye. Its effects are easily masked and largely unrecognized until late in a worker's career, when he or she is sitting at home and a neighbor has to ask the person to turn down the television.

In 2010, the Bureau of Labor statistics reported that 12 percent of all reported illnesses were related to occupational hearing loss, which equates to more than 18,000 workers who experienced significant hearing loss related to work.

Safety professionals must recognize the significant impact hearing conservation has on an employee. Most bones will heal, lacerations can be stitched, but once hearing is lost, it's gone forever. As the next generation of workers enters the workforce, we need to take a step back and look at how we manage hearing conservation and industrial noise exposure by getting back to the basics.

The Tipping Noise Scales

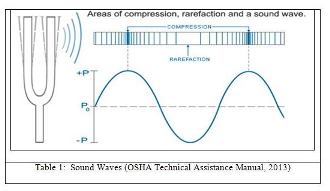

So, what is noise? To understand noise we first have to understand sound. Sound, as defined by Merriam-Webster's Dictionary, is mechanical radiant energy that is transmitted by longitudinal pressure waves in a material medium (such as air) and is the objective cause of hearing, see Table 1. Noise, conversely, is defined as any sound that is undesired or interferes with one's hearing of something.

Measured in decibels, so appropriately named after the telecommunication pioneer Alexander Graham Bell, noise is gauged utilizing units of sound pressure. There are three commonly used weighting scales for measuring decibels in industry. They are the A, C, and Z weighting.

The "A" weighted scale, which is abbreviated as dBA, has been adopted by OSHA as its weighting is thought to provide a rating of industrial noise that indicates the injurious effects such noise has on human hearing, according to the OSHA Technical Assistance Manual, 2013. "A" weighting follows the frequency sensitivity of the human ear at low levels. This is the most commonly used weighting scale, as it also predicts quite well the damage risk of the ear. Sound level meters set to the A-weighting scale will filter out much of the low-frequency noise they measure, similar to the response of the human ear.

"C" weighting (dBC) is more flat among the majority of frequencies with drop-offs at the higher and lowest frequencies. "C" weighting is typically not used for industrial noise but does have implications when conducting peak sound level surveys.

Last is the "Z" weighted scale, or "Zero" Weight. It is used when surveying total noise and has zero weighting, as the name would imply. The "Z" scale is rarely used in industrial safety applications but is useful during total noise evaluations.

The trivia question always arises on the "B" weighting. "B" weighting follows the frequency sensitivity of the human ear at moderate levels, used in the past for predicting performance of loudspeakers and stereos, but it is not used for industrial noise, so in short is not used in industry. Most of the time it is left out.

The Noise on the Regulations

Next, let's discuss rules and regulations. There are three major noise standards primarily maintained by OSHA, the National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health, and the American Conference of Governmental Industrial Hygienists (ACGIH). In the spirit of compliance programs, we will be looking only at OSHA's 29 CFR 1910 Subpart G for Occupational Noise Exposure. Specifically, let's look at occupational exposure limits set by OSHA. First is the Action Level (AL) of 85 dBA over an eight-hour time weighted average (TWA). This is the level at which it is estimated that 50 percent of the population will experience some hearing loss. When an employee is exposed at the Action Level (85 dBA eight-hour TWA), the employer is required to provide at no cost to the employee:

- Appropriate hearing protection (employees who have not had a Standard Threshold Shift, or STS, are not required to wear hearing protection);

- a written Hearing Conservation Program; and

- audiometric testing.

It should be understood that OSHA utilizes an exchange rate of 5 dBA, which means that every 5 dBA the noise increases, the intensity of the noise doubles.

At the Permissible Exposure Limit (PEL) of 90 dbA, eight-hour TWA, 100 percent of the population will start to experience hearing loss. When an employee is exposed at or above the PEL, the employer is required to:

- Provide appropriate hearing protection at no cost to employees;

- issue appropriately rated hearing protection to reduce exposure to below 85dBA, and employees are required to use it;

- through engineering and administrative controls, employers must attempt to reduce noise exposures to below the PEL;

- have a written Hearing Conservation Program; and

- conduct audiometric testing.

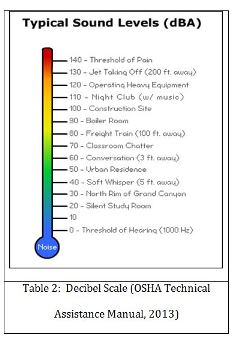

A Ceiling Limit (CL) of 115 dBA has been established. No employee shall be exposed in excess of 115 dBA of sustained noise for more than 15 minutes over a 24-hour period. Lastly, 140 dBA is the maximum instantaneous level for impact noise not lasting longer than one second in duration. Table 2 shows examples of different decibel "A" levels.

Assessing Noise

Understanding what the rules are is only half of the battle with noise. The other half is assessing noise levels. This can be done in a multitude of ways, however, for the best results, I always recommend consulting with a certified industrial hygienist (CIH) or other noise professional (e.g., a sound engineer) who is competent in noise evaluation. (As a side note for those interested, there are continuing education opportunities and publications available from the American Industrial Hygiene Association and the Council for Accreditation of Occupational Hearing Conservation about industrial noise exposure and monitoring. I highly encourage interested professionals to take a look into professional development programs and publications.)

To assess noise, you will need three basic items:

1. A personal noise dosimeter

2. A field calibration tool

3. A Type 2 sound level meter

These items can range from about $1,000 to over $12,000, depending on manufacturers, vendors, and end user specifications, such as intrinsically safe options. A few settings to remember when setting up a field noise instrument under the OSHA settings are:

1. OSHA uses a 5dBA exchange rate.

2. Frequency rating (weighting) should be on the "A" scale.

3. Meter response should be set to "Slow."

4. Criterion level should be set at 80 dBA.

5. Threshold should be set at either 80 dBA for assessment of a hearing conservation program or 90 dBA for assessing for the need for administrative or engineering controls.

It is important to remember to attempt to capture the worker's entire work shift for the best and most accurate results.

Controlling Hazardous Noise

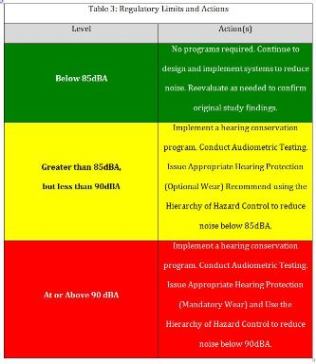

Once the data have been gathered and calculated, action may be required as part of the OSHA 1910.95 occupational noise exposure standard, depending on the noise levels mentioned in the regulatory portion of this article summarized in Table 3.

Employers have the obligation to provide workplaces that are free from recognized hazards. So then, what do we do about excessive noise? Well, let's go back to the basics by utilizing the hierarchy of hazard controls:

- Substitution/elimination. The first thing we always want to attempt is elimination or substitution of the offending process. Ask yourself the question, is it feasible to eliminate the processes in favor of one that is produces less noise?

- Engineering. Examples include noise enclosure, insulation, and/or application of acoustical absorbent material.

- Administrative. You can use job rotation or a policy that reduces noise exposure.

- Personal protective equipment. This includes ear plugs, canal caps, and ear muffs.

All too often it is seen that institutions will jump right to PPE while bypassing the other components of the hierarchy, however, this is not the course prescribed by OSHA—think of it more as a Band-Aid on a bigger wound. This furthermore solidifies the importance of involving safety in the design of new processes. Simple adjustments in the design phase can help eliminate or reduce the amount of nuisance noise. However, that is a discussion for another article.

Conclusion

Industrial noise is almost always a fact of production. As professionals in this field, we need to keep a keen and educated eye on industrial noise and how it affects our workforce populations. By reducing noise exposures, we succeed in conserving one of life's most precious resources.

This article originally appeared in the March 2019 issue of Occupational Health & Safety.