Improving In-Plant Safety with Fixed, Automated & Moveable Barriers

The right combination of barriers throughout a facility can protect employees.

- By Walt Swietlik

- Apr 01, 2022

Large industrial facilities, expansive warehouses, and massive distribution centers can be dangerous places for employees. Material handling vehicles, machining equipment, and fall hazards in such facilities all present unique safety challenges—especially when labor supply is tight, and shifts may be operating short-handed.

Forklifts, automated guided vehicles (AGVs), pallet jacks, and other materials handling vehicles are necessary to move products in bulk or efficiently from storage to shipping. Yet, these in-plant vehicles can be dangerous for workers on foot inside a plant. Forklifts alone were involved in nearly 7,300 reported accidents in 2020. There were 78 reported deaths due to forklift-related incidents in 2020.

According to OSHA, falls are among the most common causes of serious work-related injuries and deaths. In fact, slips, trips, and falls account for nearly 700 deaths each year. Fall protection continues to be one of OSHA’s Top 10 most frequently cited violations, but machine guarding is routinely part of this annual list, too. More than 1,100 violations were uncovered in 2021.

Many of these incidents could have been prevented with proper training and the right in-plant safety equipment. Specifying the proper barriers for the facility can help mitigate the daily risk employees encounter.

Reducing Floor Accidents with Fixed Barriers

Unlike painted yellow lines, physical barriers can help prevent forklifts from striking pedestrian traffic. Physical barriers are much harder to ignore, and serve additional functions as well. Beyond separating employees from automated processes and dangerous workspaces, barriers may also be used to protect production equipment and/or the building itself from damage by forklifts, AGVs, or other vehicles.

Many manufacturers rate industrial barriers based on their ability to stop an impact of 10,000 pounds at 4 mph—which has been an industry standard for more than 30 years. While this rating provides a meaningful reference for a specific load at a specific speed, it fails to define several key variables:

- How is the barrier’s performance affected as the mass of the impacting vehicle increases?

- How is the barrier’s performance affected as impacting vehicle’s speed increases?

- How severely was the barrier damaged by the impact? Is replacement necessary?

- How much did the barrier deflect during impact? Did it stop the load soon enough to prevent injury or damage?

To fully address these questions, a test methodology has been developed to quantify specific application variables and determine barrier ratings in terms of total kinetic energy absorption, instead of a specific mass and speed.

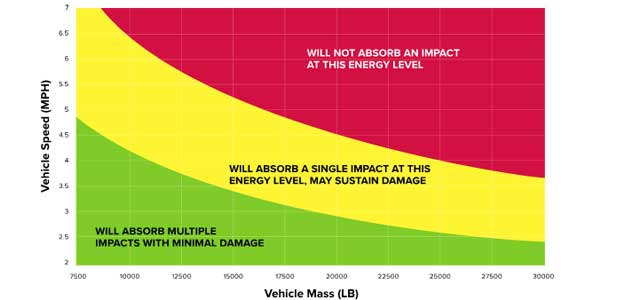

Called BLAST (short for ‘’barrier load and speed testing”), it is centered on the formula for kinetic energy (KE = ½mv2, where m=mass [weight] and v=velocity), which considers both the weight and speed of the impacting object to help determine the most appropriate barrier based on the application. Below is a kinetic energy chart used by some companies that manufacture industrial safety barriers.

The chart separates the barrier’s impact rating into three different areas, keeping in mind that differently rated barriers will have different kinetic energy charts.

The green area shows levels of testing where the barrier wasn't damaged and is capable of being impacted again. As shown in the chart, a forklift weighing 17,500 pounds (including the load it is carrying) traveling at 3 mph is going to be able to hit a barrier with minimal damage to the barrier, while keeping employees or product on the other side safe.

However, that same forklift traveling at 4 mph will fall into the chart’s yellow area, which means the barrier will stop the load, but could potentially sustain damage or inflict injury.

The red area shows where the impact energy exceeds the barrier’s maximum rating. In these cases, like if the 17,500 pound forklift was traveling at 5 mph, the impact from the vehicle cannot be fully absorbed and the barrier would not be able to stop the load—indicating that this barrier should not be used for this application.

Limiting Exposure with Automated Barriers

Whether it’s an industrial facility that uses robotic welding arms or a distribution center that utilizes automated stretch-wrapping machines, there are several potentially dangerous work cells that employees often work with or near. In these examples, having access to the work cell is necessary when a machine is powered down, but can be disastrous for the human worker when the machine is performing its task.

This is where automated barriers come into play. Unlike presence-sensing devices such as light curtains and laser scanners, perhaps the most significant benefit of an automated barrier door is it provides a physical barrier that can protect employees by restricting access to dangerous machine movement and containing the process. This is particularly important for processes such as robotic welding, where sparks and debris can become hazardous for nearby employees or machine operators. It’s also important in automated tasks like stretch wrapping, in which inertia keeps machinery in motion even after it’s been shut down.

The most advanced roll-up automated barrier doors offer high-speed, high-cycle technology, as well as PLe safety rated non-contact interlock switches and controls. Most automated doors function from the top down, but some have been designed to operate from the ground up. This allows machine operators to easily interact with the process utilizing overhead cranes to load and unload large, heavy pallets. They are also a great option for interaction points that have a very limited space.

Preventing Falls with Reciprocating & Retractable Barriers

More facilities are growing upward instead of outward to better utilize the existing footprint. However, this comes with risk as falls from heights are more dangerous to workers and product.

To help supplement OSHA regulations, many companies look to organizations like the American National Standards Institute (ANSI) for “best practice” guidelines. ANSI promotes voluntary consensus standards that are widely recognized as comprehensive, up-to-date, and reliable when it comes to workplace safety. Compliance with ANSI standards ensures that companies are implementing the most advanced safety standards in their respective industries.

ANSI standard: Specification for the Design, Manufacture, and Installation of Industrial Work Platforms (MH28.3: 2009), states: any gate providing access opening through the guards for the purpose of loading and unloading material onto a work platform shall be designed such that the elevated surface is protected by guards at all times. Gates that swing open, slide open, or lift out, leaving an unprotected opening in the guarding, are not acceptable.

According to the ANSI standard, companies must provide full-time protection when loading and unloading materials from an elevated platform—there can be no exposed areas where an employee could potentially fall. As a result, many companies are seeking a solution to secure elevated work environments.

Dual reciprocating barriers are becoming increasingly popular for this application since they create a controlled access area in which the inner gate and outer gate cannot be opened at the same time. Leading models use a link bar design that ensures both gates work in unison; when the outer gate opens to allow pallets in, the inner gate automatically closes to keep workers out. After the pallet is received, mezzanine-level workers open the inner gate to remove material from the work zone while the outer gate closes to secure the leading edge of the platform.

In addition, OSHA standard 1910 subpart D: Walking-Working Surfaces was developed to help prevent dangerous falls from heights or slips and trips on the same level (working surface). Most of the rules within Walking-Working Surfaces became effective in early 2017 with several more phased in before the start of 2019. Equipment standards on slip, trip, and fall hazards hadn’t been revised since they were first adopted in 1971, so this was a necessary update.

Walking-Working Surfaces also requires that barriers must not be lower or deflect below 39 inches. For fixed barriers, a 39-inch height would be acceptable. However, there must be extra height added to barriers that deflect. This is key for retractable barriers that are often used at loading docks that have an open dock policy, which can expose employees to a fall of 4 feet or more out of the dock door.

Chains at a loading dock should not be used in this instance as they are not strong enough to stop forklifts and typically sag well below the 39-inch requirement. It’s important for facility managers or safety managers to specify a retractable barrier that stretches across the entire width of the dock opening and one that can stop any forklift that might run into it.

Barriers for All Applications

Worker safety is essential, especially during times of labor shortages. The right combination of barriers throughout a facility can help ensure the workforce is properly protected from in-plant vehicles, machines, and falls.

The use of fixed, moveable and retractable barriers can augment painted yellow lines with a physical barrier. Automated barriers can help prevent workers who mistakenly interact with potentially dangerous robotic or machining processes. Reciprocating barriers on the edges of elevated work platforms can help prevent dangerous falls from heights. Facility managers and safety managers who seek out and specify the right barriers for each area of the building are protecting the company’s most valuable asset—its workers.

This article originally appeared in the April 2022 issue of Occupational Health & Safety.