Effective Chemical Safety Training Through Safety Engineering Training

Teaching employees to manage their own safety and their team’s safety does not produce a reliable outcome.

- By Paul Baumgardner

- Dec 08, 2022

Think of the last thing you’d like to hear when at work: “Mr. Safety, I think we have a problem!”

It is just after lunch, and this is how you are greeted by the operations supervisor who is now standing in your office doorway. There he is, at a half-run stance, gripping the dusty four-inch binder that contains those affected work area’s coffee-stained, stiff, yellowing safety data sheets. Just behind him, you can hear someone shuffling through the first aid kit in the adjacent breakroom, fumbling with the eye-wash station bottles by the kitchen sink.

Even after the morning shift’s successful tailgate safety meeting where everyone seemed alert and interested in your training (also thankful for the pizza reward last Friday) this is still how you and the poor soul (still unknown to you right now) are going to spend the rest of your afternoon. How could this happen, with all your creative and interesting chemical safety training you have been driving home to this group of well-intentioned workers? It just makes no sense at all!

Well actually it does make sense. It makes more sense than what you and I may want to admit. The training has simply been ineffective in controlling this type of an outcome. Whether or not the incident is a near-miss, non-recordable or recordable incident, it is still an accident.

“There absolutely must be a control problem,” you say to yourself. Now you are onto something! Let’s follow through with that logic for a moment.

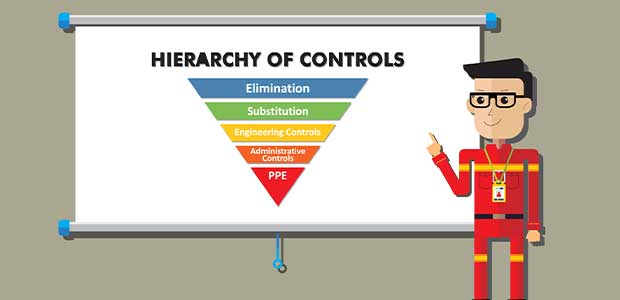

The National Institute of Occupational Safety and Health published the “Hierarchy of Controls” as a tool for safety professionals to use in our safety management system designs. The problem is that many times, we only seem to use about half of this important model.

While many have spent a career in health, safety and environmental (HSE) engineering, management has been in the lower tiers of the hierarchy (administrative controls and PPE), rather than in the upper tiers (elimination, substitution and engineering controls).

Since the 1980s, safety practitioners have been trained that accidents are preventable, rather than accepting accidents as an expected daily occurrence. The problem has only been exacerbated by the disconnect between safety engineering (top tiers) and safety management (lower tiers).

Teaching employees to manage their own safety and their team’s safety does not produce a reliable outcome. Instead, we need to teach our employees to engineer out their affected work systems’ hazards within those environments daily.

This is the only way to truly reduce risks: by removing, mitigating by replacing or isolating the hazard through a physical control. This is accomplished by operating first within the top three tiers of the hierarchy then relying on the lower two tiers as lines of last defense. In practice, incorporate the following into your next chemical safety training.

Elimination

Start by pulling out that list of hazardous chemicals from your Toxics Release Inventory (TRI) annual report. From that list, ask the line workers to consider what chemicals they perceive are either completely needless in the process or what use reductions could be made using the same chemical.

They may reveal critical information that could help to keep them safer while reducing your annual TRI totals. You could potentially have a two-for-one benefit of decreasing both human hazards and environmental hazards simply by asking this question.

Substitution

From that same list, ask the workers to imagine that any one of those chemicals is suddenly not available to them due to chemical inventory problems, chemical manufacturing logistics or operating capital problems. Ask them what alternative chemicals they would consider using. They may gift you with a wonderful idea for something less hazardous, less expensive or novel for that work system.

This outcome has happened to me more than once in railcar cleaning facilities, chemical laboratories, environmental field decontamination and even with weapon cleaning solutions during my younger soldiering days in the U.S. Army.

Engineering Controls

Ask the line workers what they would like to see automated in chemical handling, to the extent that they would not have to make direct contact with the chemical. Trust me: They have already thought of this, especially if there are totes, supersacks and drums in their processes. When they give you answers that sound like engineering ideas, that is exactly what they are. The plant engineer and you can help them to refine those ideas. Watch those engineering controls manifest out of your most highly valued, critical-to-operations professional: the line worker who just wants to go home safely.

Administrative controls and PPE are still necessary. That is why they are carefully included in the hierarchy of controls model; however, the idea is to make those two lower-tiered controls superfluous to the work system is a safety net. Let the top three tiers do the heavy lifting.

When you harness your line workers’ experiences and expertise of their work environments, your systems are better, and your employees are safer.

Instead of using that valuable time that you would normally use to track down a safety video or download a safety brief for their chemical safety training, invest it into your employees’ own creative thinking. At the end of the day, the true chemical safety engineer is the line worker who simply wants to get the job done safely and efficiently.

This article originally appeared in the December 1, 2022 issue of Occupational Health & Safety.